Androna / Andarin : The Oxford Project

Androna / Andarin : The Oxford Project

The Site

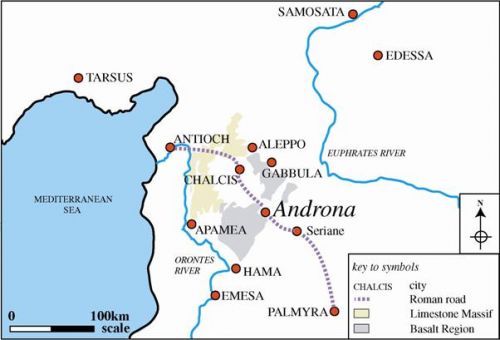

Androna, modern al-Andarin, is first attested as a mansio on the Chalcis-Palmyra route by the late 3rd century AD. Preliminary exploration was carried out in 1905 by the Princeton Archaeological Expedition under H.C. Butler. The site was viewed within a wide regional context in the 1930s by R. Mouterde and A. Poidebard’s aerial survey of the so-called ‘Limes of Chalcis', and more recently by the Syrian-French Marges Arides survey. Androna is an outstanding example of a very large late antique kômê, so identified in a 5th–6th-century mosaic inscription. At 160 ha, it is of massive size for a village, and had certain urban features, such as two sets of circuit walls and large extra-mural reservoirs. Its communal buildings included a kastron, a Byzantine bath, and nearly a dozen churches. Another bath was built in the Umayyad period. The entire space within the circuit walls is filled with collapsed buildings best seen in aerial photographs and satellite images. More than 50 Greek inscriptions, mostly of the 6th century and mentioning a total of ca 30 individuals, are known. In the 13th century (1225) the Arab geographer Yakut wrote that the site was in ruins.

Androna, situated on the western edge of the north Syrian steppe, between Aleppo and Hama, lies between coastal and semi-desert climates in a zone with only 250-300 mm rainfall. Its expansion, from perhaps a simple mansio, required the installation of qanat/reservoir irrigation systems, probably as part of a deliberate development programme, possibly linked to nearby militarized cities such as Chalcis, although there is no epigraphic evidence to support direct state activity at Androna itself. The growth of this large settlement towards the end of Roman rule in the Levant has wide historical, social and economic implications.

The International Project

The current archaeological work at Androna 1997-2007 aims to distinguish and date its developmental phases and to place it within its environmental context. This international project is being carried out by three independent teams from the Syrian Department of Antiquities (director Dr. R. Ugdeh), the University of Heidelberg (director Prof. C. Strube), and the University of Oxford (director Dr. M. Mango). Faced with a large site, these teams have concentrated in key areas in its centre and on its periphery. Following topographical survey (1997), excavation began (1998) in the centre of the site of three prominent communal/public buildings, two of them dated by inscriptions: the kastron of 558-9 (Heidelberg), the Byzantine bath of ca 560 (and the street between them) (Oxford), and an Umayyad bath (Syrian team). Excavation of domestic complexes (one dated 583/4) began in 2001 (by Heidelberg) and 2005 (by the Syrian team). Two key areas on the site's periphery have been investigated – the two sets of circuit walls (by Heidelberg) and the extra-mural reservoirs (by Oxford).

Photo R. Mouterde & A. Poidebard, Les Limes des Chalcis, Paris. 1945, pl. CXI.

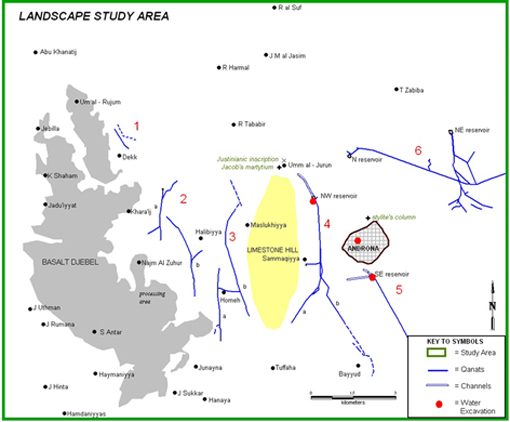

Oxford's Study of Water Use

Within the project's overall scheme, Oxford's work has concentrated on Androna's water management and agriculture. Accordingly, we have excavated the Byzantine bath as well as major parts of the SE and NW extra-mural reservoirs, and planned two other reservoirs. We have also carried out a survey of water flow in the two excavated reservoirs and one of the six qanat systems. Oxford’s landscape study of the area around Androna, started in 2004, has produced evidence of agricultural activity and small-scale nearby settlement, as well as a martyrium and a stylite’s column.

Funding

The Oxford project at Androna has been funded by generous grants from the Craven Committee Oxford; St. John’s College Oxford; Council for British Research in the Levant London; Dumbarton Oaks Washington, DC (Harvard University); Research and Equipment Committee Oxford; Society of Antiquaries London; McCabe Family Foundation; British Academy London; Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies London; Joanna Sturm; History Faculty Oxford; Meyerstein Fund Oxford; Near Eastern Studies Programme Oriental Studies Oxford.

Contact Details

For further information, please contact:

Dr. Marlia Mango (Director) - marlia.mango@sjc.ox.ac.uk

Priscilla Lange (Research Assistant) - contact via fergus.millar@classics.ox.ac.uk

Marlena Whiting (Research Assistant) - marlena.whiting@lincoln.ox.ac.uk

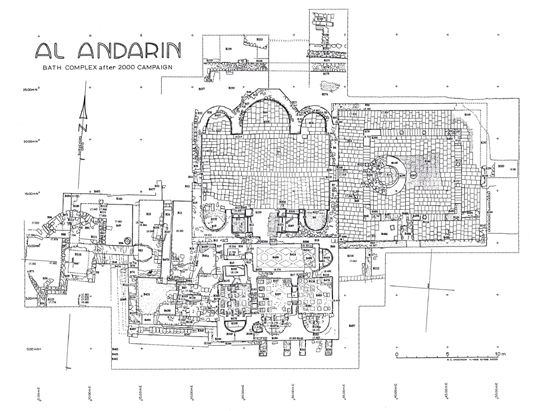

Plan drawn by R. C. Anderson © All rights reserved

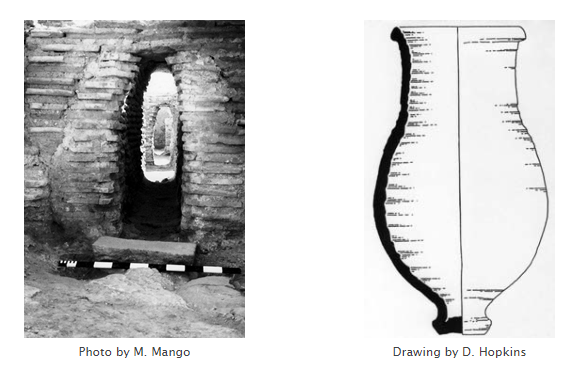

The basalt and brick bath, built in ca. 560 by Thomas (who also constructed the large kastron opposite in 558-9), according to a Greek verse inscription on its lintel, was excavated 1998-2001. Its plan, ca 23 x 40 m, is divided into four parts: a peristyle entrance court; a north frigidarium with a symmetrical layout, five apses and two rectangular pools; a south tepidarium and a caldarium comprised of a brick complex of apsed rooms with six semicircular and rectangular pools; and a west service area. Architecturally, it is larger than the village baths of the north Syrian Limestone Massif. It more closely resembles in layout the Byzantine city bath at Zenobia on the Euphrates and the Umayyad baths at Androna and at Qusayr Amra in Jordan.

The water of the Byzantine bath at Androna was supplied by a saqiya-operated well situated in the west service area and a carafe-shaped cistern in the entrance court. While the former filled the bath’s pools, the latter provided drinking water. The jars used on a chain (pot garland) to lift water above ground level account for nearly half the diagnostic sherds of pottery found in the bath. Water lifted from the well was conveyed to one or more water tanks positioned above the bath. Used water was drained from the pools by two systems, one running to the south of the bath, the other to the north, both apparently emptying into a second, disused well 11 m deep. The cistern water was collected from the roof of the peristyle entrance court via vertical pipes at its four corners.

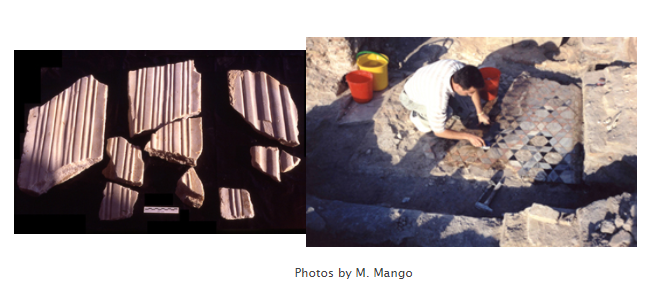

By far the greatest amount of decorative material found in the bath was 500 kg of 19 types of marble (over half of it Proconnesian from the Sea of Marmara) and other decorative stones used for pavements, door mouldings, champlevé carving, other wall revetments, opus sectile work, the carved enclosures of the cold pools, a marble fluted basin, and a small marble statue. The south rooms had white tessellated pavements. The entrance court was decorated with figural paintings, of which only the lower parts remain on the west wall. The frigidarium was at least partly decorated with glass wall mosaics, while the caldarium had brightly coloured wallpaintings of abstract patterns and Greek inscriptions enclosed in wreaths.

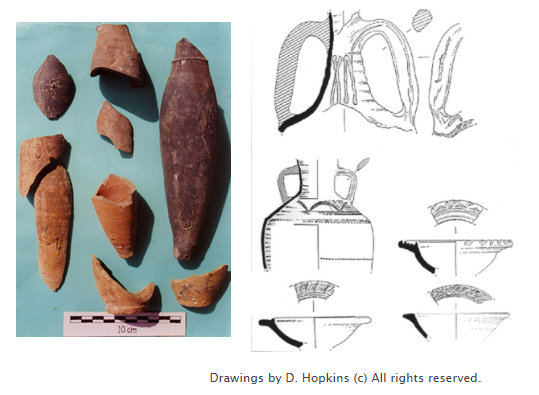

Excavated finds appropriate for a bath include ceramic spindle-shaped unguentaria for oil, some stamped, and numerous glass perfume flasks and small drinking goblets. Altogether, the pottery is mostly Late Roman/Byzantine, with some of the transitional period from Late Byzantine to Umayyad. Nothing is definitely Abbasid. Imported wares include African Red Slip Ware and Late Roman C and D Wares. Local coarse wares include small buff bowls with decorated rims and Brittle Ware. Amphorae included Egyptian types and Riley Carthage Late Roman 1 as well as local painted and combed buff amphorae.

The bath remained in use, probably for several decades, judging by the condition of the furnaces, the amount of limescale deposits, and successive layers of wallpaintings. Eventually, when the bath went out of use (possibly following a partial structural collapse), various industrial activities were installed there, including a metal workshop in the tepidarium and a kiln in the entrance court the aisles of which were partitioned for yet other purposes; another kiln was built outside the west door of the frigidarium. This conversion of the building may have occurred in the Umayyad period, judging from the excavated pottery. In this period another bath of similar size and plan was built nearby and has now been excavated by the Syrian team. This late bath incorporated several Byzantine inscriptions in its floors and walls and its water was apparently supplied by the well of the Byzantine bath uphill from it.

Participants

The excavated Byzantine bath and reservoirs were planned by Richard Anderson with the assistance of Dr. Tassos Papacostas, Dr. Jonathan Bardill and Dr. Lukas Schacher, with contributions by Simon Greenslade, Sarah Leppard, and Stuart Randall. The bath and reservoirs were excavated by, notably, Amanda Claridge, as well as Katherine Blythe, Paul Clark, Simon Greenslade, Cassian Hall, Prof. Robert Hoyland, Dr. Carrie Hritz, Sarah Leppard, Antonietta Lerz, Dr. Marlia Mango, Prof. Cyril Mango, Dr. Anne McCabe, Dr. Maria Parani, and Dr. Nigel Pollard.

Finds were drawn by Dave Hopkins and processed by Priscilla Lange, Dr. Maria Parani, and Natalija Ristovska.

The following material excavated in the Byzantine bath is being studied:

The Greek inscriptions, by Prof. Cyril Mango, Oxford University.

The marble, by Dr. Olga Karagiorgou, Academy of Athens.

All pottery, by Dr. Nigel Pollard, School of Humanities, Swansea University.

The Brittle Ware pottery, by Dr. Agnès Vokaer, Centre de Recherches Archéologiques, l'Université Libre de Bruxelles.

The metallurgical finds of the metal workshop installed in the bath tepidarium, by Chris Salter, Materials Department, Oxford University.

Map by R. Hoyland, L. A. Schachner and T. Papaioannou.

The Landscape Study

Oxford’s study of water usage extends outside the site of Androna. While the bath and other buildings within the site obtained water from wells and cisterns, Androna’s agriculture depended on qanat-reservoir systems for irrigation. As part of our investigation, major parts of two extra-mural reservoirs have been excavated (2000-06), two other reservoirs planned (2005) and a survey of water flow within the qanat-reservoir systems carried out (2006). Excavation of the Byzantine bath produced organic and other evidence of agricultural production at Androna. Oxford’s landscape study of the area around Androna, started in 2004, has produced further evidence of agricultural activity and of settlement, including two religious establishments, a martyrium and a stylite’s column. The rectangular study area (22 x 14 km) encompasses two different terrains. To the west is a basalt djebel with traces of vine terracing. To the east of this is a limestone plain and low hill, opposite Androna, flanked by qanats thought to irrigate grain fields. Our landscape study will allow us to integrate extra-mural excavated areas with the surrounding terrain so that we can see how the various units of exploited land relate to each other and to Androna itself.

Evidence of Agricultural Production

|

Photos by M. Mango

This evidence relates to the cultivation of olives, vines, and grain, livestock rearing and possibly fish breeding. On and near the site we have found olive mills and olive pits used as fuel, while a pre-Islamic Arabic text (the Mu`allaqa of Amr Ibn Kulthum) records Androna's wine production. Materials sampled during excavation of the Byzantine bath and processed by flotation produced evidence of coniferous and deciduous wood used as fuel, as well as bread wheat, durrum and barley (including preparation materials). Study of the wide range of animal bones recovered by excavation of the bath suggests the local breeding of sheep, goat, and pig for butchering, while fish bones of bream, mullet and catfish have been identified. It is possible that one reservoir was used for fish (catfish?) breeding. Equipment recovered within and recorded outside Androna includes olive and flour mills, troughs (possibly multi-purpose), vats, other containers and, possibly rollers used in oil processing.

Photograph taken by R.C. Anderson. (c) All rights reserved.

Irrigation: Qanats and Reservoirs

The qanat, a subterranean form of aqueduct, taps into an aquifer and, through a system of galleries reached by a series of vertical shafts, leads water to the surface and deposits it in a reservoir or other form of basin. Among the six qanat systems within our study area, five (nos. 1-5) flow south-north and one (no. 6) east-west. Four of these may have originated within our study area. At least three (nos. 4-6) of the six qanat systems have a total of four reservoirs. We have partially excavated two of these and planned the other two. Our survey of water flow levels in 2006 concentrated on the two excavated reservoirs and qanat no. 4 located just west of Androna that conducted water to the NW reservoir.

Photo M. Mango

Both excavated reservoirs, situated NW and SE of Androna, are constructed of limestone, are shallow (2.50-3 m) and measure 61 x 61 m. Both have multiple stone inlet and outlet channels And both were elaborately decorated, one with large niches, the other with figural sculpture suggesting they may have been used for aquatic displays for a festival like the Maiumas. Dating the reservoirs and qanats can clarify the nature of the settlement at Androna, that is, whether the large investment in the qanat-fed system was pre-Roman, Roman or Byzantine, publicly or privately funded.

NW reservoir. This reservoir, fed by qanat no. 4, has an inlet channel with one lateral channel branching off to the east which conducted water to a nearby field. Opposite the inlet, the outlet system has upper and lower channels conducting water northwards. The upper channel turns east shortly beyond the reservoir, while the lower channel continued for more than 972 m in a northwestern direction. It apparently carried water towards Umm al-Jurun ca 3 km from Androna where stood an imperial boundary stone set up in the names of Justinian and Theodora (527-548), marking the property “of the martyr Jacob”. Nearby may lie his martyrium.

|

|

Photos by M. Mango

SE reservoir. This reservoir situated opposite the south gate of Androna, was fed by qanat no. 5. Water was conducted first to a settling pool above the main inlet, but could be diverted through two lateral inlet channels which led to nearby fields. The water that was deposited in the reservoir flowed out the opposite side through an outlet system apparently removed in modern times Traces of the outlet channel were recorded by magnetometry (2006) at a short distance outside the reservoir and continuing for 300 m in a northwesterly direction. Early aerial photographs, satellite images and kite photographs show a canal (?) running between the reservoir and the area of qanat no. 5 to the west.

While H.C. Butler (1905) placed the SE reservoir in the 2nd century AD on stylistic grounds, a radiocarbon reading on charcoal contained in a cement sample removed from the reservoir's floor gave a date in the 6th to 7th century. Analysis of sediment samples will date the period of abandonment. Both sets of dates would bracket agricultural production dependent on irrigation prior to modern times. A late Roman date for the reservoir is in part confirmed by the evidence of the fine ware pottery we gathered on the outlet side where water was conveyed to a manured cultivated field. The ca 220 recesses (30 cm deep) at the base of the walls of the reservoir suggest that it was also used as a vivarium for fish breeding, probably of catfish (Silurus), preserved for export. Salt was available locally from the lake at Gabbula just to the north of Androna.

Photo M. Mango

Settlement

Oxford's landscape study seeks to understand Androna's growth within its environmental context. Two interconnected questions are addressed by the study: how far did the large site of Androna (160 ha) dominate the land around it and did the lesser sites that lie near Androna develop as its satellites as a consequence of its own expansion?

In 2005-06, in addition to recording qanats and reservoirs, we mapped the location of all known sites within our study area. The 19 buildings identified at six main sites were planned and 131 loose architectural (including inscribed lintels) and agricultural finds recorded. Pottery (over 7000 sherds) was collected at 13 sites and offsites, using a series of grids forming 10 x 10 m collection units. Most fine ware pottery collected is Late Roman while a relatively small proportion is of glazed medieval wares. Interviews were conducted with farmers to enable us to compile a modern settlement and agricultural history of the area.

Stylite’s column. At 300 m outside the north wall of Androna lies a fallen stylite’s column which once stood 10 m high. The identity of the holy man who once sat on it is unknown. Among the remains is an olive mill suggesting the production of oil possibly at an agricultural property of a shrine or hermitage erected at the column. In future we intend to extend our limited excavation there (1999) to determine in more detail the character of this site.

|

|

|

|

Photo by R.C. Anderson. (c) All rights reserved |

Photo C. Mango |

Martyrium. Near the Justinianic boundary stone at Umm al-Jurun lies a mounded area (ca. 120 x 120 m) strewn with decorative architectural members including columns, column bases, thresholds, door jambs, capitals and part of a Proconnesian marble slab with cross. This may have been the shrine of the Martyr Jacob referred to in the boundary inscription. The body of a reliquary, possibly related to Jacob, found in a nearby village may come from this site. Traces of other buildings lie near the mound. Other loose finds which are numerous suggest agricultural activity.

Contributors and Participants

Contributions to our study of the irrigation systems and the exploitation of Androna’s hinterland have been made notably by Richard Anderson (especially kite photographs, from 1998); Dr. Tyler Bell and Prof. Andrew Wilson (1998-9); Prof. Tony Wilkinson (SE Reservoir, 2001); Jenny Emmett (flotation, 2001); Prof. Michael Decker (1998-9, from 2003); Dr. Carrie Hritz (especially satellite study, from 2003); Prof. Robert Hoyland, (plotting sites and offsite features, interviewing local inhabitants; 2004-06); Simon Greenslade, Sarah Leppard, and Dr. Anne McCabe, (recording buildings and loose finds 2005); Khalid Mohammed, Theodore Papaioannou, Stuart Randell and James Stockbridge (pottery collection, 2005); Alex Johnson (magnetometry, 2006); Bruce Magee and Dr. Lukas Amadeus Schachner (water survey, 2006).

For reservoir excavation, see Byzantine Bath.

Photo B. Magee

In addition, the following material is being studied:

The water flow of the irrigation installations, by Dr. Lukas Schachner Oxford University.

The animal bones, by Priscilla Lange, Oxford University.

The fish bones and charcoal, by Caroline Cartwright, British Museum.

The botanical material, by Prof. Mark Robinson, Oxford University.

The late antique agriculture of Androna, by Prof. Michael Decker, South Florida University.

Agricultural equipment used at Androna, by Dr. Anne McCabe, Oxford University.

Modern settlement and agriculture, by Prof. Robert Hoyland, Oxford University.

The landscape study pottery, by Elisabeth Pamberg, University College, London University.

The stylite complex, by Dr. Lukas Schachner, Oxford University

Radiocarbon and Optical Stimulated Luminescense analysis are being carried out at RLAHA, Oxford University.

Current International Project

'Baths, reservoirs and water use at Androna in late antiquity and the early Islamic period' in Residences, Castles, Settlements. Transformation processes from late antiquity to early Islam in Bilad al Sham (German Archaeological Institute, Damascus, 2008), 73-81.

'Al-Andarin/Abdrona: an Early Byzantine settlement in Central Syria' for Vortrag/online for XXX.DOT (Freiburg, Germany)

M. Mundell Mango, ‘The Centre In and Beyond the Periphery: Material Culture in the Early Byzantine Empire’, in: Byzantina-Metabyzantina. La périphérie dans le temps et l’espace. Dossiers Byzantins 2 (2003), 119-28.

C. Strube, ‘Androna/al Andarin. Vorbericht über die Grabungskampagnen in den Jahren 1997-2001’, Archäologischer Anzeiger (2003), 25-115.

A. Vokaer, La Brittle Ware en Syrie: production et diffusion d’une céramique culinaire de l’époque hellénistique à l’époque omeyyade. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles. (Brussels, 2005)

A. Vokaer, 'Brittle Ware Trade in Syria between the 5th and 8th centuries', in M. Mundell Mango, ed., Byzantine Trade (4th - 12th centuries). Recent Archaeology of Local, Regional and International Exchange (Aldershot, in press).

Other Work at Androna

H.C. Butler, Architecture, Section B, Northern Syria. Syria: Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria 1904-1095 and 1909. (Leiden, 1920), 47-63.

B.W.K. Prentice, Greek and Latin Inscriptions, Section B, Northern Syria. Syria: Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria 1904-1095 and 1909 (Leiden, 1922), nos. 909-45.

R. Mouterde and A. Poidebard, Le limes de Chalcis. Organisation de la steppe en haute Syrie romaine (Paris, 1945), 15, 61-63, 171-4, 217, 229-40, pls. CX-CXIII.

Inscriptions Grecques et Latines de la Syrie (Paris, 1955), nos. 1675ter – 1713.

B. Geyer and M.-O. Rousset, ‘Les steppes arides de la Syrie du Nord à l’époque byzantine ou la rouée vers l’est’, in: B. Geyer, ed., Conquête de la Steppe et approriation des terres sur les marges arides du Croissant fertile (Lyon, 2001), 111-21.

M. Griesheimer, ‘L’occupation byzantine sur les marges orientales du territoire d’Apamée de Syrie (d’après les inscriptions de Taroutia emporôn et de Androna)’, in: B. Geyer, ed., Conquête de la steppe et approriation des terres sur les marges arides du Croissant fertile (Lyon, 2001), 137-41.

R. Jaubert, F. Debaine, J. Besançon, M. al-Dbyiat, B. Geyer, G. Gintzburger, M. Traboulsi, The Arid Margins of Syria. Land Use and Vegetation Cover. Semi-arid and Arid Areas of Aleppo and Hama Provinces (Syria) (Lyon, 1999), 16-9, 32-4.

H. Salame-Sarkis, ‘Syria grammata kai agalmata’, Syria 61 (1989), 322-5.