Feasting in the Bayeaux Tapestry

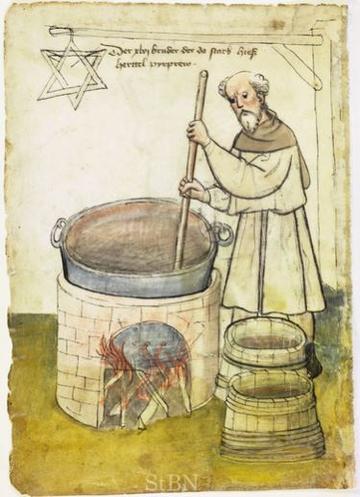

You probably know that the English people drank quite a lot in medieval times – but did you know that it is estimated that in 1300 an average man drank nearly a gallon of beer per day? People across Europe drank heavily in the era – the Vikings of Scandinavia have been described as, ‘men of some thirst’ – but England in particular was known at the time for her peoples’ heavy consumption of food and beer, and the church didn’t approve. Bishop Wulfstan in 1014 blamed overeating and drinking for the fall of all England. Aside from medieval monasteries, the majority of beer was brewed in homes, domestically. Who made this homespun beer? The medieval surnames ‘maltster’ and ‘brewster’ are in the female form, indicating that nearly all home-brewing was conducted by women!

Anglo-Saxons drank an awful lot of beer. We know from historical records that they even allowed children to drink a weakened version. A good host was one whose guests left with the smell of beer on their breath.

We often hear people say that drinking beer was safer than drinking water but recent research has claimed that water in the era was mostly safe to drink – the Anglo-Saxons just liked ale – on an ‘oceanic’ scale!