The Dig: Further Reading

With its six-month long teaser campaign and much anticipated New Year release for The Dig, Netflix has joined a long tradition of film makers who appreciate that the discipline of archaeology is uniquely suited to satisfy the global public’s need for stories which explore who we are and where we come from.

If, like us, you thoroughly enjoyed watching The Dig but you wished it had allowed more screen time for the excavation and finds and more dialogue elucidating as to who the Anglo-Saxons were, then look no further! We have curated this list of recommended readings and resources just for you (just for us too).

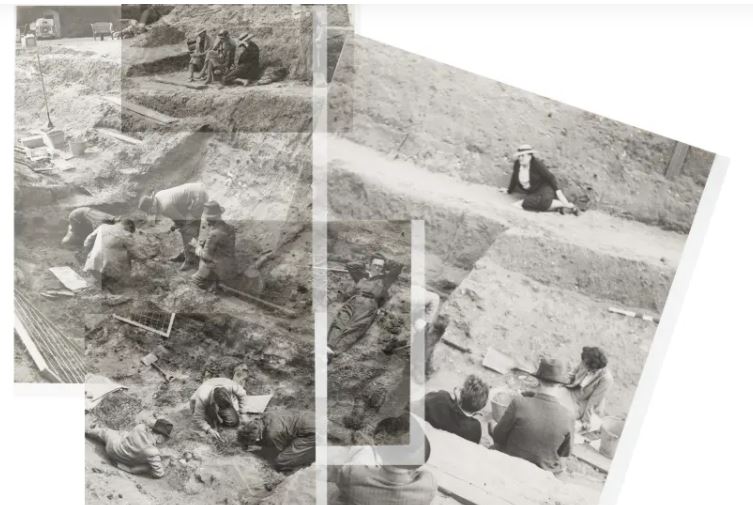

Firstly, we would like to introduce you to DPhil student Beth Hodgett (Pitt Rivers Museum and Birkbeck College). Beth’s research investigates the photographic archive of archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford (1886–1957). Crawford was a prolific photographer; today approximately 9,600 of his photographs are housed in the School of Archaeology’s Archive. This includes a collection of his photos taken during the 1939 excavation at Sutton Hoo.

To celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Sutton Hoo excavation, Beth ran a social media takeover for Antiquity on the 25th July 2019 to draw out some of the stories in Crawford's photographs. Beth has also published on this subject in Antiquity:

Beth Hodgett (2019) ‘Rear elevation’ and other stories: Re-excavating presence in O.G.S. Crawford’s photographs of the 1939 Sutton Hoo Excavation. In Antiquity (open access).

In Crawford's photographic archive there are 124 photographs of the site. By tracking the dates and times that each of these photographs was taken, it is possible to reconstruct Crawford's activity; at times he was taking photographs as rapidly as every two minutes. Beth was able to create collages which capture the wider frame and so for the first time we can see the spread and interaction of people and activity across the site. For example:

Figure 1. Social space at Sutton Hoo. This photograph is worthy of comment for the higher than normal ratio of women to men. Peggy Piggott is on the far right. Edith Pretty sits in the wicker chair in the foreground, while the ‘lady from Australia’ reclines on the far side of the trench.

Of course, Sutton Hoo was not the only richly furnished burial in 7th century England. From the middle of the 7th century we can see that it was actually women and girls who had the most eye-catching grave goods. We have evidence of this from two sites near Oxford, both investigated by Professor Helena Hamerow.

Helena Hamerow, A Byard, E Cameron, A Düring, P Levick, N Marquez-Grant and A Shortland (2015) A High-status seventh-century female burial from West Hanney, Oxfordshire. In the Antiquaries Journal (registration required)

In 2009, a metal-detector find of a rare garnet-inlaid composite disc brooch at West Hanney, Oxfordshire, led to the excavation of an apparently isolated female burial sited in a prominent position overlooking the Ock valley. The burial dates to the middle decades of the seventh century, a period of rapid socio-political development in the region, which formed the early heartland of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex. The de luxe brooch links the wearer to two other burials furnished with very similar brooches at Milton, some 10 km to the east and only c 1km from the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex at Sutton Courtenay / Drayton, just south of Abingdon. All three women must have been members of the region’s politically dominant group, known as the Gewisse. The burial’s grave goods and setting add a new dimension to our understanding of the richly furnished female burials that are such a prominent feature of the funerary record of seventh-century England.

Figure 2. Composite photo of the West Hanney brooch. On the left we see the brooch as excavated, the central image is after conservation, and the right image shows a digital ‘reconstruction’ by the School’s photographer, Ian Cartwright. Image credit: I. Cartwright.

Figure 3. Close up of the garnet inlaid cloisonné composite disc brooch.

Image credit for figures 3 and 4: I. R. Cartwright.

Figure 4. A photo of the burial assemblage discovered at West Hanney, including two fragments of glass (apparently from the same vessel), a chalk and spindle whorl, iron knives,and, two small ceramic vessels (most likely cups).

Helena Hamerow (2020) A Conversion-Period Burial in an Ancient Landscape: A High-Status Female Grave near the Rollright Stones. In: The Land of the English Kin, Studies in Wessex and Anglo-Saxon England in Honour of Professor Barbara Yorke.

In March 2015, a metal detector user uncovered several early medieval artefacts from land adjacent to the Rollright Stones, a major prehistoric complex that straddles the Oxfordshire—Warwickshire border (O.S. SP 2963 3089). He alerted the Portable Antiquities Scheme and the well-preserved burial of a female, aged around 25–35 years and aligned South-North, was subsequently excavated. The grave—which was shallow, undisturbed (apart from a small area of disturbance near the skull caused by the detectorist) and produced no evidence for a coffin or other structures—contained a number of remarkable objects indicating a 7th-century date for the burial. This was confirmed by two samples of bone taken for AMS radiocarbon dating, which produced a combined date of 622–652 cal AD at 68.2 per cent probability and 604–656 cal AD at 95.4 per cent probability (OxA-37509, OxA-37510). The burial lay some 50 m northeast of a standing stone presumed to be prehistoric in date, known locally as the ‘King Stone’. This burial and its remarkable setting form a significant addition to the corpus of well-furnished female burials which are shedding new light on the role of women in Conversion-period England, about which Barbara Yorke has written so compellingly.

Helena Hamerow (2016) Furnished female burial in seventh‐century England: gender and sacral authority in the Conversion Period, in Wiley Online Library (registration required)

A new, refined chronology for graves and grave‐goods in Anglo‐Saxon England has revealed a marked increase in well‐furnished female burials beginning in the second quarter of the seventh century. The present study considers what gave rise to this phenomenon and concludes that the small number of royal nuns and abbesses who figure so prominently in written accounts of the Conversion were part of a wider, undocumented change in the role of women that began several decades before the founding of the first female houses. It is argued that these well‐furnished graves reflect a new investment in the commemoration of females who came to represent their family's interests in newly acquired estates and whose importance was enhanced by their ability to confer supernatural legitimacy onto dynastic claims.

Recommendations for further study:

If this subject has captured your interest, why not think about studying here with us? The 11-month Master of Science Degree in Archaeology provides an opportunity for students to build on their knowledge from undergraduate studies and to specialise in a particular area of archaeology, while also offering an excellent foundation for those wishing to continue towards research at doctoral level. It also offers transferable skills which are beneficial to a range of professional roles.

In the Medieval Archaeology stream you will benefit from the teaching and supervision of specialists who cover the periods from late antiquity to the 17th century. The stream focuses on the material remains of medieval Europe, including Britain, and the Byzantine World. You will engage with both established and new approaches to archaeological and other forms of evidence, including written sources and art, as well as with current debates regarding how such evidence should be interpreted.

Tutorial Question Examples:

- How has the excavation of other barrows and flat graves at Sutton Hoo, and the excavations of the princely burial at Prittlewell changed our view of Mound 1?

- What effect has the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard had on our interpretations of ‘princely’ and royal burials?

Get in touch with us if you want to know more!