New research reconstructs the identity of victims from one of the earliest victory celebrations in Europe.

New research reconstructs the identity of victims from one of the earliest victory celebrations in Europe.

New research published in the journal Science Advances challenges previous theories about prehistoric conflict by offering a detailed look into the lives and deaths of victims of what could be one of the earliest victory celebrations in Europe. The study, which is led by Dr. Teresa Fernández-Crespo, a Distinguished Researcher at the University of Valladolid (Spain) and a Research Associate at the School of Archaeology, and is co-authored by Professor Rick Schulting, reconstructs the identity of these victims through innovative multi-isotope analysis.

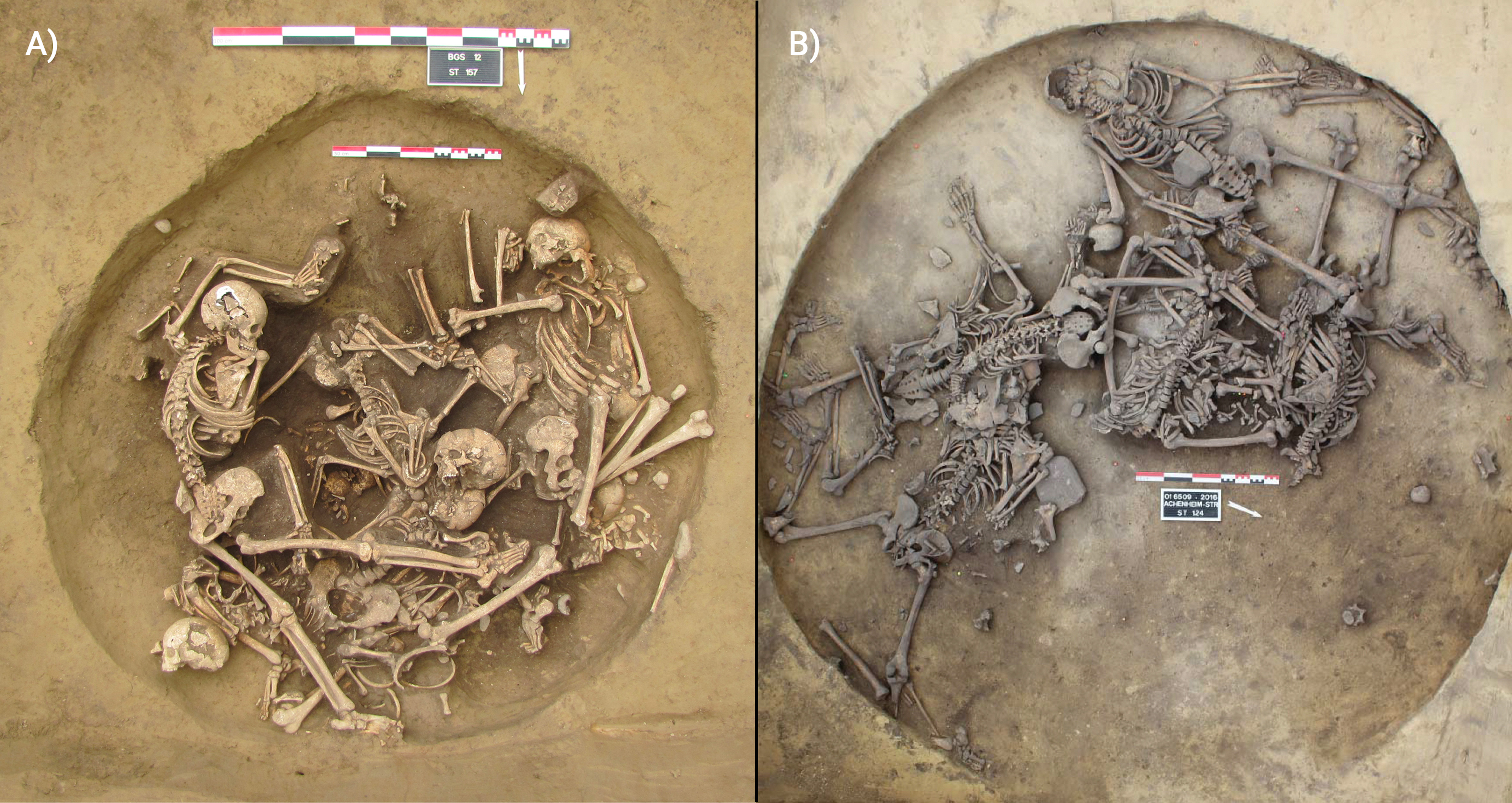

The research focused on two Late Middle Neolithic sites in Alsace, northeastern France: Achenheim and Bergheim, dated to around 4300–4150 BCE. Archaeologists discovered human remains in circular pits, including complete skeletons with multiple signs of "unnecessarily excessive" violence, also known as overkill. The pits also contained isolated segments of severed left upper limbs. This unique combination of evidence does not align with typical massacres or executions previously documented in the European Neolithic record.

To solve the mystery, the research team used a multi-isotope approach to reconstruct the victims' identities. By analyzing stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur from the bone and tooth collagen, as well as oxygen, carbon, and strontium isotopes from tooth enamel, they were able to reconstruct their diet, social background, and geographic origin. The study compared these "victims" with other individuals from the region who had received conventional burials, referred to as "non-victims". Samples from animals and plants were also analyzed to establish a local isotopic baseline.

The results reveal significant isotopic differences between the victims and non-victims. The victims' isotopic profiles suggest they experienced greater mobility, a more variable diet, and potentially higher physiological stress, pointing to a substantially different lifestyle. This supports the hypothesis that they were outsiders.

The findings also show clear differences between the complete skeletons and the severed limbs, particularly in the sulfur isotope values. This suggests that their different treatment may be linked to their geographic origins. The severed upper limbs had consistently low sulfur isotope values, which matched those of the supposed non-victims in northern Alsace. This could indicate that these individuals came from that area. In contrast, most of the complete victim skeletons had higher sulfur values, compatible with an origin closer to southern Alsace.

The study proposes a striking interpretation: the severed limbs were trophies from enemies who fell in battle and were brought back to the village for public display. The individuals with complete skeletons, meanwhile, may have been captives brought back alive to be cruelly tortured and sacrificed in victory celebrations—a form of "political theatre" to reinforce social cohesion and dehumanize the enemy.

These findings suggest that the ritualised violence and trophy deposition at the Achenheim and Bergheim sites represent one of the oldest and best-documented examples of victory celebrations in European prehistory. The study offers a new perspective on Neolithic conflict and the identity of its victims, moving beyond simple massacres to reveal complex, culturally specific rituals of triumph that may have been a key aspect of ancient warfare. The researchers believe these events were not just acts of violence, but also acts of power reaffirmation, revenge, and commemoration of the fallen.

Fig. 1. Overhead views of late Middle Neolithic violence-related human mass deposits of the Alsace region, France, analysed in this study. A) pit 157 from Bergheim “Saulager” (credit: F. Chenal); and B) pit 124 from Achenheim “Strasse 2, RD 45” (credit: P. Lefranc).

The research was funded by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions individual grant from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, awarded to Dr. Fernández-Crespo. It was a collaborative effort between the CNRS, Aix Marseille University, and Minist Culture, LAMPEA in Aix-en-Provence, France; the School of Archaeology at the University of Oxford, UK; the Department of Chemistry at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium; the Department of Archaeology and New Technologies at Arkikus, Spain; ANTEA-Archéologie, France; the University of Strasbourg, France; UMR 7044 Archimède, University of Strasbourg, France; and Inrap Grand Est, France.